How Technicolor Images of Tumor Samples are Changing Cancer Research

Catherine Wu, MD

You can ruin a perfectly good Sunday afternoon trying to find Waldo in a 5,000-piece jigsaw puzzle, even with his red-striped shirt and hat. Imagine a terrible twist: The pieces of your puzzle have faded to black and white. Your only hope is a special lamp that reveals the pieces that formerly were red. You gather these pieces into a pile and wonder, "Where’s Waldo?"

For a long time, scientists faced a similar scenario daily in their laboratories. Armed with the ability to identify only a few markers in cells on a slide, they tried to find answers. What kind of cells are these? What proteins are driving this cancer? How can we stop it from growing?

Now, new tools are making it possible to see the whole puzzle, fully assembled and in technicolor, and to discover the secrets that hide within it. Hundreds of colors glow from slides holding whisper-thin samples of tumors, painting stunning landscapes and pinpointing individual cells with star-quality identities. At Dana-Farber, several researchers are using these tools to understand how the immune system behaves in tumors.

"We are seeing absolutely entrancing images that are expanding our understanding of what happens when we harness immunity against a tumor," says Catherine Wu, MD, chief of Stem Cell Transplantation and Cellular Therapies and Lavine Family Chair for Preventative Cancer Therapies at Dana-Farber. "Seeing is believing."

Kai Wucherpfennig, MD, PhD

The Need for Tools to Visualize Immune Cells

For nearly 150 years, scientists have been staining tissue samples with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and looking at them under the microscope. The pink and purple stains reveal individual cells and cellular structures and today are used by pathologists to diagnose cancer.

In the 1940s, a technique called immunohistochemistry gave researchers a window into the molecular makeup of the cells. Blue and brown stains indicated the presence of specific proteins in cells on the slides. Later, immunofluorescence enabled staining of slides with fluorescent red, green, and blue colors to reveal the presence and location of specific antigens.

Using these techniques, researchers were able to see a short list of cancer-related markers on a slide, such as estrogen receptors and progesterone receptors in breast cancer samples. The tools led to discoveries that became valuable in the clinic to guide treatment selection for patients and more.

In the lab, however, researchers needed more.

"We used to do these single antibody stains, showing you some brown cells on some background, which doesn't tell you anything about cell-to-cell communication," says Kai Wucherpfennig, MD, PhD, chair of Cancer Immunology and Virology at Dana-Farber. "Even with five or six markers it’s hard to discover something new."

Over the past two decades, "omics" techniques such as bulk and single-cell sequencing enabled researchers to learn more about which genes are turned on in tissues and individual cells isolated from tumor samples, providing clues about which new markers might be helpful to study. But these techniques lack key information: exactly where the markers of interest are in the tumor.

For example, suppose single-cell sequencing indicates that T cells in a tumor sample are producing factors that can kill cancer cells. This could mean that the T cells are actually killing cancer cells. Then again, it might not.

Judith Aguido, PhD

"If the T cells show features of killer cells, it might indicate action against the tumor – but only if the T cells are inside the tumor and touching the tumor cells," says cancer immunology investigator Judith Agudo, PhD.

Seeing the Whole Puzzle

About five years ago, a new technology emerged that enabled researchers like Agudo to be able to identify and pinpoint killer (and other) cells with little more than a glance at a slide. The technique, called spatial proteomics, produces images that reveal the location of distinct proteins – such as those that can kill cancer cells – in every cell on a slide at once.

To create the images, scientists float antibodies across the slide. The antibodies bind to specific proteins in the sample. Each antibody is tethered to a protein-specific fluorescent substance, enabling its signal to be captured by a fluorescence microscope. By using the technology serially, applying and washing away collections of fluorescent probes, every known protein in the proteome can be lit up on a single slide.

"It's a beautiful process. You just set it up in the evening, let it run overnight. In the morning, you get your picture," says Wucherpfennig.

Complementing this technology is another, called spatial transcriptomics, that similarly identifies the RNA present in each cell on a slide. It provides a readout of which parts of the genome are being read and used to assemble proteins, providing investigators with a detailed view of the types of cells that are present and how they are functioning. This technology is newer, with commercial products only available within the past few years.

"I don't think we appreciated how much the spatial dynamics of the immune system matter," says Agudo. "Immune cells are mobile, and we need to know everything about every cell if we want to understand how the immune system responds to a tumor or treatment."

Discovering an Immunological No-Man's Land

This layered image illustrates why immunotherapy alone may not be enough to treat triple-negative breast cancer. T cells (blue) cluster on the right and cannot enter certain areas. Layering on additional markers reveals that these restricted areas are populated by dormant (quiescent) cancer cells (yellow). This finding suggests opportunities to develop new strategies to target these cells, which can evade both chemotherapy and immunotherapy. Image courtesy of Pilar Baldominos Flores, PhD, Agudo Lab.

Dana-Farber researchers are already using these tools to make discoveries that could someday change the way cancer is treated. One example comes from Agudo's lab.

Agudo was studying triple-negative breast cancer, a form of breast cancer that is notoriously difficult to treat. In human patients, the disease consistently resists treatment with both chemotherapies and immunotherapies.

Studies of human samples of triple-negative breast cancer indicated that the tumors contained T cells that had the potential to fight the cancer. But few patients with the disease were benefiting from immunotherapy.

Agudo probed more deeply using spatial profiling tools to study mouse models of the disease. This work was done back in 2022, when spatial tools were just emerging. Even with the smaller number of probes available at that time, she was able to differentiate active T cells from exhausted ones, and active cancer cells from quiescent ones.

The images she produced, in partnership with Kun Huang, PhD, scientific director of the Molecular Imaging Core at Dana-Farber, showed that the T cells were not evenly distributed in the tumor. Rather, they were clustered into dense areas, with other areas devoid of active T cells.

"These images were a 'wow' moment for me," says Huang. "First of all, they are so pretty. But also, the biology is shown so dramatically. With these tools, we can see hundreds of markers distinctly, ones that were not visible before and that enable us to see the biology more deeply."

Further inspection of the active proteins in the images revealed that the regions of the tumor that lacked active T cells were different from the regions infiltrated with them. The spaces contained tumor cells that were quiescent, not actively growing. These quiescent cancer cells survive immunotherapy and also resist chemotherapy.

"We couldn’t see it before, but these are the cells that give rise to relapse," says Agudo. "Now we need to use that information to benefit patients."

Additional research has revealed that existing drugs might be able to kill these quiescent cells and could potentially be used in combination with immunotherapies or chemotherapies to improve the anti-cancer effects. The research is still in pre-clinical stages and is not yet ready to be tested in human trials, but Agudo and her team are working on it.

Changing the Cellular Conversation

David Reardon, MD

Agudo’s research revealed one way that cancer influences the immune system’s behavior, but treatment also affects immune cells. Both Wucherpfennig and Dana-Farber’s David Reardon, MD, clinical director of Dana-Farber’s Center for Neuro-Oncology and Alperin Family Chair in Neuro-Oncology, have studied tumor samples taken from patients during clinical trials before and after treatment using spatial profiling tools to learn more about how the immune system is altered.

The trials involved patients with glioblastoma, a form of brain cancer that has poor survival rates. One of the trials evaluated immunotherapy alone against immunotherapy plus radiation.

Clinical studies have shown that radiation therapy could induce an immune response in some cancers. In the laboratory, experiments have shown that radiation therapy plus immunotherapy with drugs that unmask the immune system, called immune checkpoint inhibitors, can enhance that immune response against the cancer.

Reardon initiated a deeper investigation into the cellular mechanics of these responses. His team collected tumor samples before and after treatment. They then used spatial profiling tools to determine how the treatments changed the tumor microenvironment and the activity of immune cells.

"Fundamental to any cancer treatment is validating its mechanism of action, what it's actually doing within the tumor," says Reardon. "These spatial technologies are making it possible to look at these mechanisms at a level that has not previously been possible."

Reardon found profound shifts in the immune microenvironment in the samples retrieved from a small subset of patients. Prior to treatment, there were few T cells, with those present clustered near blood vessels. But after treatment, they increased in number and had spread deeply into the tumor.

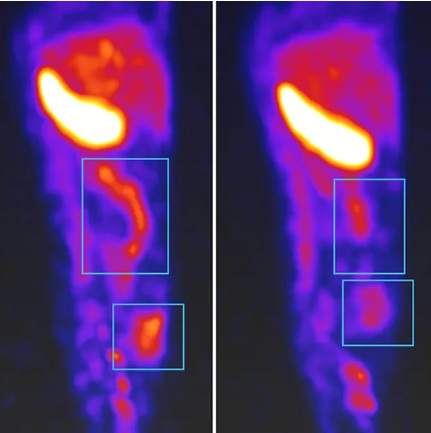

This paired image shows how combining radiation therapy with immunotherapy can help mobilize the immune system against glioblastoma, an aggressive brain cancer. Left: Before treatment, T cells and other immune cells cluster around blood vessels and are held back by an immune-suppressing tumor environment. Right: After combination therapy, immune cells have moved deep into the tumor in a sample from the same patient. Images by Kun Huang, PhD, Molecular Imaging Core.

In addition, immune cells of various types seemed to be working together, moving closer to one another. By illuminating proteins that reveal the current activities of T cells, the team was able to confirm that T cells in the sample were poised to kill, as opposed to being exhausted and unable to kill.

The findings could influence the development of future clinical trials, providing evidence that radiation does stimulate a stronger immune response. But according to Reardon, this is just the beginning.

"With these multiplex spatial profiling tools, we are poised to learn how to use the many treatment strategies we have available – immunotherapies, chemotherapies, cell therapies, biologics – effectively and in the right combinations to help our patients," he says.

Reimagining Immunotherapies

Wucherpfennig also applied spatial profiling tools to samples taken during a clinical trial for patients with glioblastoma. The trial was a first-in-human test of an oncolytic virus to learn more about how the treatment changes interactions between tumors and immune cells.

When testing a novel medicine that has never been used in this patient group before, the ability to examine a genome's worth of markers across a tumor sample enables the team to learn much more about how the drug is affecting the cancer.

"We can ask more biological questions in addition to outcome questions," says Wucherpfennig. "We want to discover the principles, going deeper into how this complex system of immune cells behaves."

The results of Wucherpfennig's study aren’t published yet, but he is asking questions he's never asked before, seeing things he's never seen before, and dreaming of the next generation of immunotherapies.

Whole-Body Imaging of Inflammation

Inflammation is a sign of disease that may soon be detected in a whole body scan using technology being developed in the lab of Dana-Farber’s Mohammad Rashidian, PhD. The team has built a positron emission tomography (PET) probe that targets markers on human immune cells. The probe gives off a signal detectable on a PET scan, showing where immune cells are gathering in the body.

The team plans to use this tool initially to detect a rare but dangerous inflammatory condition in the heart that can occur with some cancer treatments and can be difficult to diagnose without an invasive heart tissue biopsy. Plans for a first-in-human clinical trial of this technology are in the works.

The Tools Behind the Images

Dana-Farber has two microscopy labs with spatial profiling tools available for research. The Molecular Imaging Core is co-directed by Kai Wucherpfennig, MD, PhD, and Judith Agudo, PhD, (bottom right) with Kun Huang, PhD, (top left) serving as scientific director. In addition to supporting research, the core partners with instrument developers to create customized biomarker panels for Dana-Farber research.

The Pathology Core Lab is directed by Kathleen Burns, MD, PhD, chair of Pathology, and supported by research science manager Renchin Wu, MD, PhD, and Namrata Singh, PhD, (top right). It supports both research and clinical studies. Huang and Wu anticipate rapid advances in spatial profiling tools – technologies that map the location of cells and molecules within tissue – in the coming years.

By Beth Dougherty